Today I am featuring a crossover post that was initially shared yesterday on Postal History Sunday. I felt it had enough general interest and farm content that some folks who subscribe here, but not there, would enjoy it. For those of you who subscribe to both Substacks, I thank you and hope you enjoy this one at least once, if not necessarily twice.

Either way, it’s your call!

The Buzz

Our farm has maintained anywhere from one to four hives of honeybees each season for several years now. Prior to that, another beekeeper brought a hive or two to our farm and maintained them. Our primary purpose is to secure pollinator services for our fruit and vegetable crops. Edible honey for ourselves and family is our secondary purpose.

We also work to provide habitat for wild pollinator populations. We maintain areas on the farm that include brush piles, bush lines and areas we do not till because wild space provides habitat. For those who are interested in some of the ways we work with pollinators and beneficial organisms, you can check out this recent article on the GFF Substack.

We have had a difficult time over-wintering our bees but we finally managed to keep one hive alive through this past winter. Our farm is surrounded by corn and soybean fields, so we are unable to protect our bees from exposure to insecticides, which lessens our chances of success. That means we are usually in the position where we need to acquire new bees every year.

There are two main options when we are looking to start (or restart) a bee hive. We can either buy a nucleus colony (often referred to as a “nuc”) or we can buy a package.

The nuc includes frames with comb, worker bees and a queen. In our experience, each nuc will have three or five frames. There can be anywhere from 8,000 to 12,000 bees in a nuc along with brood and some stored pollen and honey. The entire nuc might weigh 25 to 35 pounds, which does not make it a very good candidate for sending via the US Postal Service - though I understand it can be done. We are more familiar with picking up nucs without mail carrier service.

A package is often referred to as a “3 pound package,” which references the weight of the bees in the container. The actual weight of the container, food source and bees will be more than that. Each package contains a queen, in her own personal cage, and about 9,000 bees (a typically quoted number is 3,000 bees per pound). In addition to the bees, there is a tin can with sugar water to provide the bees with some sustenance. The queen often has food in her cage as well.

With a total weight that is probably around five pounds, packages are a much easier weight and size to ship. You can see an example of a package that was mailed via the USPS in the first image shown above. One of the sides with the shipping label is shown below.

Our package was sent in a wood frame box that included screened sides. Obviously, no one wants the bees to leave their package while they are traveling. And, you might notice the notation in pen that says “Call for P/U” (call for pickup) which indicates that our post office called us to come to the post office to get our bees. Our phone number was included on the package so the postmaster at our post office could give us a call. Postal regulations require that bee packages must be picked up at the post office and that the phone number of the recipient must be on the package.

One side of the package has address information and evidence of postage paid. The bees were sent by USPS Ground Advantage, which is the only alternative for a package of bees. They are not allowed to be carried by air service. The big “G” at top left on the label also indicates “Ground” service.

If a person wanted to have only a queen bee sent in the mail, she could be sent via air service. Being royalty has its perks, I guess.

The current regulations for shipping bees have not, to my knowledge, changed much for many decades. In fact, the typical containers to ship a package of bees has also stayed the same for quite a long time. The only thing that has changed, of course, has been the cost of postage and the fees required for a sender to mail live bees.

There is plenty of evidence that queen bees were being shipped from location to location using the mail service in the late 1860s and early 1870s. This is about the time beekeeping journals like A.I.Root’s “Gleanings in Bee Culture” started. These early periodicals often include advertisements offering queen bees. There are also references to shipping nucs, but I am not certain those would have been sent via the US Post Office. I suspect a person could spend some significant time hunting for the origins of shipping bees via the mail before being very certain they had found the earliest attempts.

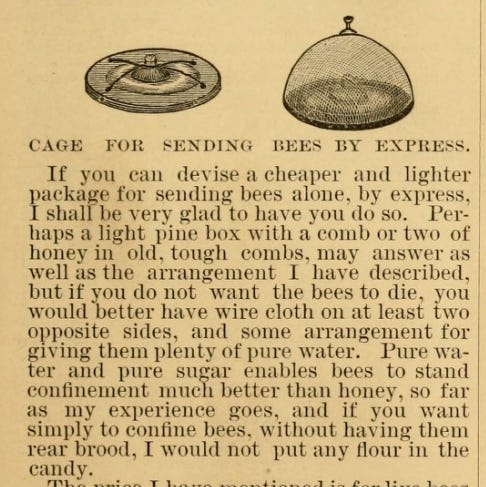

The first recorded attempts to mail live bees in a package through the mail that I can find were based on a proposition by A.I. Root in his May 1879 edition. In that same publication, Root mentions Mr. Langstroth’s efforts to create a cage for mailing queen bees, which seems to indicate that shipping bees via the mail might still be somewhat new (I cannot be sure of this). He also discusses the possibility of shipping live bees with a queen (our modern day package) in the introduction (page 163) of that same edition.

The name Langstroth is deeply connected to the methods and hive construction used by most modern day beekeepers. We are among those who use Langstroth design hives that allow for more mobility. This encouraged commercialization of apiaries and led to the interest in shipping bees. Therefore it is likely that we would find records of some of the earliest shipments of live bees (queens) through US Mail in the 1850s - if they exist.

The motivation for shipping bees came from the common issue of hive loss for northern beekeepers during the winter months. Root argued that if Southern beekeepers could figure out a way to send packages of bees to Northern beekeepers, they would develop a good business. Meanwhile, Northern beekeepers would have a chance to get new hives started that would produce honey much more quickly than if they had to rely on building up hives reduced by cold weather.

Root’s suggestion that a way could be found to ship packages was taken up almost immediately by readers. The June issue of Gleanings reports that two beekeepers had attempted to send him packages with live bees, but most bees died in that attempt. I suspect further reading would probably reveal additional progress.

For those who are interested, Wyatt Mangum writes in the American Bee Journal that they seek out and collect old bee shipping containers for packages of bees. He also shares another package shipping crate in a different article. In both cases, the package features a wood frame with a mesh covering. Their shapes may be different from the present day package, but they are not terribly different otherwise.

By 1947, the US Department of Agriculture reported that 1,375,000 pounds of package bees were shipped (538,651 packages) , an increase of 6% from the previous year. During the same time period, over 1 million queens were shipped. While the US Post Office is not identified as the shipper for these live bees, the government monopoly of mail service makes it likely that most of this was carried by them.

I guess A.I. Root’s idea led to something.

The USPS claims that 96% of all mail is delivered within one day of the “specified standard” according to this 2023 report. And some honeybee suppliers make the claim that 90 to 95% of their bees arrive in good shape. But the reality is that there is much that can go wrong with a shipment of bees.

Our delivery percentage is 67% on an admittedly low sample size (three shipments over two years). Our first package this season arrived with very few live bees remaining. They could have been exposed to too much heat, or cold, or whatever.

In our case, Mann Lake, the supplier of the bees, shipped us a replacement and filed the claim with the USPS for the loss. Other suppliers may purchase the insurance with the USPS but ask you to file the claim if there is a loss.

We opted to try mailed packages because the locations where we could order and pick up nucs are still a significant drive for us. We are hopeful for more local options to purchase bees in the future because we are aware that our success rate is likely to be higher with bees that overwinter closer to where we live. Ideally, of course, we’ll find a way to get bees to just overwinter with us. But the track record tells us we shouldn’t count our bees before they… um…

Speaking of hatching…

The Cheep

We have also picked up “day-old chicks” at the post office.

In our experience, the same cardboard boxes are used to ship the chicks via the USPS as they are when we go to pick the birds up from a hatchery in person. And, once again, we might prefer to purchase chicks from hatcheries that are closer to home - except that is not always an option.

To be perfectly frank, there are several Iowa hatcheries at the present time, but they are not as prevalent as they were even thirty years ago. Some of these hatcheries, like Hoover and Murray McMurray, make most of their sales to mail customers - shipping all across the country. So, depending on what you are trying to do, you are often left with the choice between a very long drive or mail delivery if you want chicks.

And, just a reminder to readers who say “Oh, the local farm store has chicks every Spring,” I must remind you that they get shipments from these hatcheries too. Most likely via the US Postal Service.

Most of the time, the chicks arrive healthy and they grow well at the farm. In fact, it’s more normal for us to have survival rates from chick to adult at or over 95% than it is to have high loss rates. For perspective, even if we hatched chicks on the farm, I would not expect a higher survival rate than this. Any time you deal with baby animals, things can happen and some of the young will not survive.

On the other hand, we have experienced the “phone call of doom” a couple of times. We now know that if a postal worker tells us “they are pretty quiet for chicks” or “I hate how smelly they are,” we are in for a nasty disappointment

We have hatched a small batch of chicks on our own, but every farm has to decide what they can and cannot do with their time and resources. We just never had the available time/labor to be self-sufficient in that way. So we rely on hatcheries. And since we can’t always purchase from a hatchery that is near by, we rely on the USPS to deliver them safely.

Unfortunately, the reputation for the USPS and its reliability has taken a few hits in recent years. First, the movement to try to run it more like a profitable business rather than a public service has discouraged efficient and effective rural mails. And, a quick news flash for you all of you… many who raise birds live in rural areas. This includes the Genuine Faux Farm.

Then there is a recent story of USPS truck that was left unattended, even though it held multiple shipments of live baby birds. For those who have interest, Wayne Youngblood recently wrote about the topic of shipping live poultry in the mail. Not only does he provide the current regulations for shipping live birds, he covers this story quite well.

He beat me to the punch on this one! Good job Wayne!

Turning up the heat

I recognize that I haven’t really provided everyone with an old cover yet and that might be making some of you a little “twitchy.” In an effort to alleviate any pain you might have endured, I offer up this illustrated advertising cover.

The cover shown above was sent under the 2 cents per ounce rate for internal United States mail. The destination is South Amana, which is part of the Amana Colonies in Iowa. South Amana is one of six communities established in 1855 (a seventh, named Homestead, was added in 1861). The Amanas were established as a communal society populated by Germans who had established a settlement near Buffalo, NY in the 1840s after having left Europe to seek a location where they would have religious freedom for their belief system.

There is, currently, a Surehatch Incubator Company in Missouri that still sells product. Whether it is the same business (or if that business has shared roots), I do not know.

The cover shown above is a bit older, mailed from Bristol, Connecticut to North Hadley, Massachusetts in the 1880s. I haven’t spent time trying to decipher the year date on the postmarks, but I can tell you it would have to be 1888 or later based on the stamp design (first used Sep 10, 1887).

Both incubators and brooders provide heat and shelter. The incubators for hatching eggs and brooder for raising the chicks until they begin to grow in feathers. Early in their lives, baby birds need help with temperature regulation and both of these devices increase their likelihood of survival.

For those of you who recognize that chicks are raised by parent birds in nature, it is certainly possible to allow hens to raise a clutch of chicks. It is up to the parent to help the babies regulate their temperatures in that case. But it is also true that the survival rate is likely to be lower.

Once again, the main motivation for incubators, brooders and mailing bees or chicks is the commercial sales model. For example, if our farm only raised eggs for ourselves and family, and sold eggs when we happened to have extra, I suspect we would let some hens raise chicks. But since we endeavor to have a certain number of eggs to sell every two weeks to a customer base, we have to do things a little differently to increase the likelihood that we will have a reliable inventory of food to sell.

And that’s why there is postal history - even if it is fairly modern in today’s Postal History Sunday - that shows how these live animals were shipped.

Thank you for joining me. I hope you enjoyed this cross posting from Postal History Sunday. We’ll get back to our regular posts later in the week. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Rob, you are the absolutely the definition of a polymath. I'd pay to see an image of a brain scan of yours. I bet it'd resemble an active bee hive.